On short summer nights, it’s hard not to notice the Vega star high in the sky. It is the brightest star of the small constellation Lyra and generally one of the brightest stars in the terrestrial sky. Vega is also designated as ⍺ Lyra (alpha) and is the main attraction of this constellation.

Vega is the Etalon Star

It is interesting that Vega was once considered the etalon star. Probably everyone who is interested in astronomy has heard about such a thing as the apparent magnitude. It characterizes the apparent brightness of a celestial object. Astronomers many centuries ago called the brightest stars the first-magnitude stars, and the weakest, barely visible to the naked eye, the sixth-magnitude stars.

Previously, the magnitude of a star was determined by eye, comparable with neighboring stars. With the development of photographic observations, apparent magnitudes began to be determined much more accurately. Fractional apparent magnitudes were introduced. Now in catalogues, the apparent magnitudes of celestial objects are usually given with an accuracy of one hundredth.

The rule was also approved that a first-magnitude star is exactly 100 times brighter than a sixth-magnitude star. In addition, the scale was continued. Zero-magnitude stars and even negative ones appeared – for brighter celestial objects than first-magnitude stars. For example, the brightest star Sirius has an apparent magnitude of -1.46. And the brightness of Venus sometimes reaches -4.60.

So, for the zero reference point of the scale of apparent magnitudes, the brightness of the Vega star was originally chosen!

Vega is not only the etalon star in brightness. It is also the etalon star in color! Vega is considered, so to speak, the whitest star. The B–V and U–B color indices of the Vega star are zero. These are the most commonly used color scales that characterize the difference between apparent magnitudes of a celestial object when observed through various light filters.

Now the catalogues indicate that the apparent magnitude of Vega is 0.03. So, in terms of visible brightness, it has ceased to be a standard. Although by eye you will never be able to distinguish by brightness a star of magnitude 0.00 and a star of magnitude 0.03.

Vega and its Motion Among the Stars

Vega shines about 40 times brighter than our Sun and is 25 light-years away from us. However, all the stars are in motion relative to each other. And in about 273 thousand years, the Sun will pass closest to Vega. The distance to it will be reduced by half. It will shine as brightly as Sirius is shining now. Vega will become the brightest star in the sky!

Watch this beautiful animation of how Vega moves relative to other stars in the sky when observed from Earth over a time interval of 2 million years. This video is best watched in the dark! Very beautiful! Throughout the video, Vega is in the center of the screen. It can be seen that 470 thousand years ago, an optical fusion of yellow Capella and red Aldebaran could be observed in the sky near Vega. In 320-360 thousand years, Vega will pass through the beautiful constellation Perseus. Also note that Vega will pass in 550 thousand years against the background of the scattered Hyades cluster. Finally, after one million years, Vega will be in the constellation of Orion, which will be greatly distorted during this time.

Vega is one of the most studied stars, and there are many more interesting things to tell about it. But I would like to dwell on other interesting features of the constellation Lyra.

Epsilon Lyrae is a Double Double Star

On a clear moonless night away from the city lights, look carefully at the faint star of ε Lyrae (epsilon), which is located near Vega. If you have very sharp eyesight, you may notice that instead of one star there are two small stars, almost merging into one.

If you still see only one star, don’t worry. Even in the simplest theatrical binoculars, the star of the Lyra looks double.

If you look at this pair of stars in an amateur telescope, then each of these two stars in turn splits into two!

It turns out that where most people see only one star with the naked eye, four stars actually shine! And everyone can see this with the help of an inexpensive telescope.

Other Interesting Objects in the Lyra Constellation

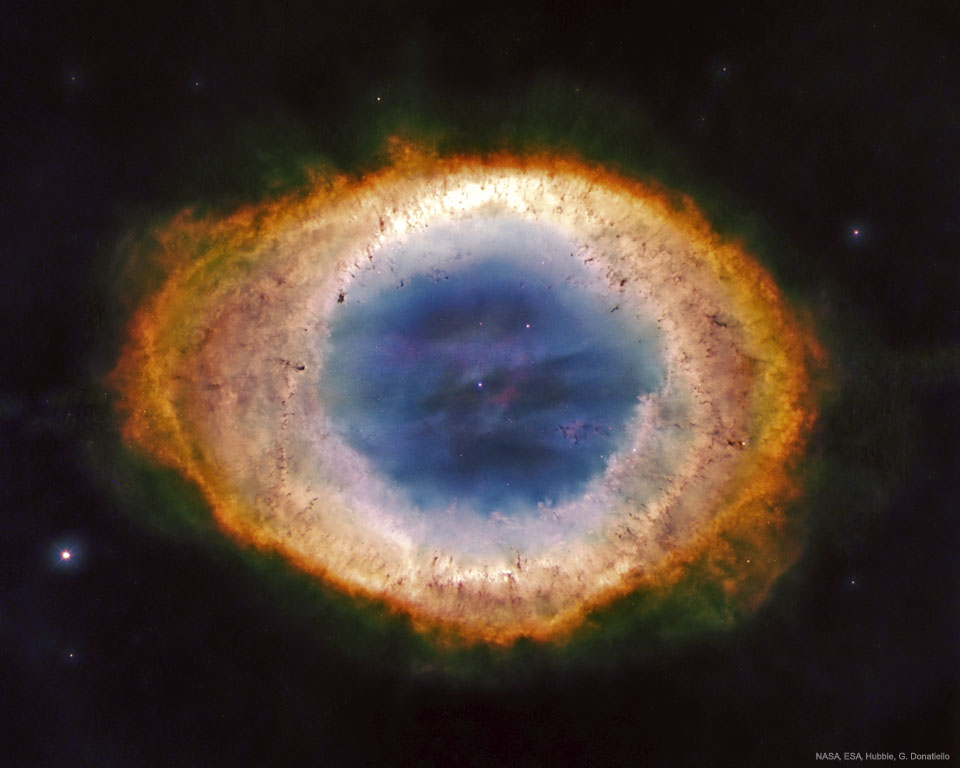

Also in the Lyra constellation is the famous planetary nebula Ring (M 57). Here we see the substance dropped from the star, which is located in the center of this nebula. This star just highlights the slowly expanding nebula. Unfortunately, I don’t have my own photo of this nebula, so I’m attaching a NASA photo:

You need to look for this nebula between the stars β and γ in the lower part of the parallelogram of the Lyra constellation. In an amateur telescope, it looks like a small faintly glowing ring.

There is also a globular star cluster M 56 in the constellation Lyra. It is not very rich in stars, besides it is lost against the background of the Milky Way. In an amateur telescope, it looks at best like a faint nebula. But in powerful telescopes it looks very impressive. The photo is not mine, since I don’t have my own powerful telescope in orbit:

Mythology of the Lyra Constellation

Lyra constellation derives its name from the Latin word for Lyre, its three-letter abbreviation is Lyr. It is small, in 52nd place out of all 88 constellations, and is one of the oldest. At the time of Ptolemy, it was included in the catalog of the starry sky (there were 48 constellations in total).

According to Greek legend, the constellation Lyra depicts a musical instrument played by Orpheus. This instrument was made by Hermes from the shell of a turtle and was so magnificent that it could enchant even inanimate objects. One day Orpheus married the nymph Eurydice, but she was bitten by a snake, and she died from this bite. Orpheus went to the Underworld to get his beloved back. Hades was delighted with his music and allowed him to pick up Eurydice, but on condition that Orpheus would not turn around on the way back. However, towards the end, he stumbled and turned around, and Eurydice remained in the Underworld forever. Orpheus spent the rest of his life wandering and playing the lyre, never marrying again. After his death, Zeus placed his Lyre in heaven.

The Arabs saw a kite or an eagle instead of a Lyre, which swoops down with folded wings. And Vega is translated from Arabic and means “falling kite”. Among the Australian aborigines, the constellation of the Lyre is known as the constellation of the Hammer Bird. In ancient atlases, the Lyre was often depicted in the claws of a vulture.

The Solar System is Moving Towards the Lyra Constellation

The constellation Lyra is notable for the fact that approximately in the direction of this constellation the Solar System is moving relative to the stellar stream in its vicinity. To be more precise, the apex is the point where the Sun moves with the planets, located in the constellation Hercules on the border with the constellation Lyra. This can be clearly seen in this beautiful animation. While the planets are orbiting the Sun, the Solar System has time to move in space, so the trajectories of the planets relative to the stellar flow in the vicinity of the Sun look like helical lines. The speed of the Solar system relative to the nearest stars is about 20 km/s. Relative to the center of our Galaxy, the speed of the Sun and the stellar flux in its vicinity is much higher. The solar system moves forward in space with its north pole, but at a certain angle. The orbit of the Sun relative to the center of the Galaxy lies almost in its plane.

The ‘Messenger’ Came From the Lyra Constellation

But that’s not all! It was from the Lyra constellation that the famous interstellar asteroid ʻOumuamua flew into the Solar System! The sun caught up with this asteroid in space and changed the trajectory of its motion, tearing it out of the stellar stream in the vicinity of our star. In this video you can clearly see how it happened.